The Give Me Comics or Give Me Death podcast is available from all your usual podcast providers, or see all episodes here

See the index for all entries in these Batman annotations here

Grant Morrison's epic Batman tale not only uses previous Batman stories for its inspiration, plot, and themes, it is predicated on the very fact that there are previous Batman stories - that everything that was printed did in fact happen. From the sci-fi madness of the Silver Age to the gritty violence of the 90s, no story was out of bounds for Morrison or for Batman himself. Grant does a decent job of weaving these parts of Batman continuity into its own story so that reading these earlier comics is not necessary to understand and enjoy it, but reading them - or at least these summaries! - will help illuminate the saga in ways that can only enhance it.

There is, admittedly, a lot to get through, so I've broken this down into two parts to make it somewhat easier to digest. This first part will focus on other Grant Morrison work, and the second on comics by other writers. Grant's comics have often tackled similar themes and ideas, and there is a crossover of many of these in most of their work for DC Comics, so in theory one could recommend reading the entire back catalogue of Morrison! Don't worry, I'm not going to do that. I'm going to focus on the most relevant comics to this run, particularly the key themes, plot points, and characters that shape it.

Arkham Asylum (1989)

Written by Grant Morrison

Art by Dave McKean

Probably the work that put Grant Morrison on the map – when released Arkham Asylum was the biggest selling graphic novel of all time (I believe Morrison claims it still is). The multitudes who picked up this prestige format comic, with fully painted art by Dave McKean, must have been bemused by the story that they encountered. Far from an action-packed adventure, or mystery solving plot, it is instead a slow labyrinthian examination of Batman’s psyche. Batman arrives at the mental institution, Arkham Asylum, at the behest of the Joker who has taken its staff hostage. Batmen enters the gothic mansion to try and resolve the situation. In there he confronts a gallery of his rogues, each partly reflecting a piece of his own personality. In flashback we also get the history of Amadeus Arkham, who founded the asylum, and this plays into why one of the doctors released the inmates from their cells initiating the whole escapade. However, it’s not particularly clear whether these events actually happen or if they all occur in Batman’s mind.

Like much of Morrison’s previous Batman work, there are no specific connections made in his Batman run to this story. In fact, one of the more interesting points of his epic tale is that really only the Joker and Talia Al Ghul from his rogue’s gallery make appearances, other key characters from Arkham Asylum; Two-Face, Scarecrow, Clayface, Killer Coc, etc, are ignored completely. However, there are some more thematic and symbolic connections:

The point of the story is to examine Batman, who he is and how he works, which is also ultimately the point of Morrison’s full Batman run but on a much larger scale. Though the main difference is that here we take a look at Bruce Wayne from the inside of his head, whereas stories like Batman R.I.P. and The Return of Bruce Wayne use the actions of other characters and Bruce’s response to them to demonstrate the key elements of the Batman character.

The key antagonist in Arkham Asylum is the Joker, who after forcing Batman to enter the asylum challenges him to a game of hide and seek – this is reminiscent of Batman R.I.P. and The Return of Bruce Wayne, where the Joker and Dr Hurt play out a metaphorical game of chess with each other, and where games, including dominos, are a recurring theme. The story also brings up the idea that the Joker is not insane, but rather “super-sane”, constantly reconstructing himself in response to the ever-changing zeitgeist. Morrison explores this in much more detail in Batman R.I.P. Furthermore, the Joker’s motivation here is not to attack Batman physically but psychologically, which is not only the motivation of Dr Hurt but also key to the conflict between him and the Joker.

The Joker’s dialogue is presented in a different colour scheme to the other characters – in this case red with a white drop shadow – a technique that is used to particular effect in Batman R.I.P.

Much of Arkham Asylum revolves around the symbolism of the tarot, which is something Morrison uses in a lot of his work – they are strongly influenced by magic and have said one of their first real uses of it was giving a tarot reading to friends and acquaintances. Whilst much less integral to the story than in Arkham Asylum there are allusions to the tarot in Morrison’s Batman run, most obviously in Batman Incorporated which reflects the Tower card – quite literally at the conclusion.

Batman: Gothic

Originally published in Legends of The Dark Knight #6-10 (1990)

Written by Grant Morrison

Art by Klaus Janson

Morrison’s second Batman story is much more conventional than Arkham Asylum, and whilst it has less to say about Batman as a character than his other work, it does have some thematic links to his later Batman run. The plot of Gothic is fairly straightforward, though its mysteries are slowly revealed with skill by Morrison. Someone is killing off various mob bosses in Gotham. The criminals, surprisingly, turn to Batman for help, claiming they know the murderer is a ‘Mr Whisper’ a child-killer who the believed they had murdered 20 years ago, and is now back wreaking his revenge. It is subsequently revealed that ‘Mr Whisper’ is Bruce Wayne’s old headmaster ‘Mr Winchester’, and that Bruce was to be his next victim until his father pulled him out of the school furious at the corporal punishment being administered to his son. To celebrate, Wayne the elder suggests they all go out to see a film – this turns out to be the infamous night Bruce’s parents are killed and his journey to becoming Batman begins. Linking events in a story back to key moments in Batman’s life; his parent’s death, the bat breaking through his window, the death of Jason Todd, is something that is used repeatedly throughout Morrison’s Batman run.

The mystery doesn’t end there – the true identity of the villain turns out to be Brother Manfred, a monk who sold his soul to the Devil in return for 300 more years of life. The machinations of Whisper/Winchester/Manfred all turn out to be an attempt to cheat his way out of the deal, as his 300 years are now up. Batman stops his plan, and the Devil – in the form of a nun – appears and takes his soul to hell. Here, Morrison has clearly solidified the supernatural into the Batman mythos, and also established the Devil (and his deal making) as existing in the DC universe, which plays a key part in his later stories with both Dr Hurt and Damian. Surprisingly though, despite one key premise of Batman R.I.P. being that all these stories happened, there are no overt references to Gothic or any suggestion that Dr Hurt and Brother Manfred share any connection.

- Morrison has often talked about superheroes in comparison with mythological gods and heroes – hence the title of his superhero analysis/autobiography book Supergods. In JLA he takes this idea literally, portraying the team as the modern-day incarnation of the Greek god pantheon; Superman is Zeus the king of the Gods, The Flash is Hermes the god of speed, and Aquaman is Poseidon god of the seas, to pick the most obvious ones. In this take Batman is Hades, the god of the dead and the underworld. Hades was depicted by the Greeks as being cold and stern, traits typically associated with Batman – though part of Morrison’s aims for the character in Batman R.I.P thru Batman Incorporated was to break him out of such restrictive characterisation. In Morrison’s Batman it’s suggested that death is a key component of the character and his mythos; not only was death of Bruce Wayne’s parents the catalyst for his transformation to Batman, but the death of those close to him (even if many are resurrected) is an almost routine occurrence and central to many Batman stories. Hades’ realm of the underworld is also something often referenced by Morrison, most obviously in the metaphor of the Batcave, but also in the notion of Batman descending into the underworld to obtain knowledge or understanding. As Batman, Dick Grayson does this twice in Morrison‘s run; when he goes deep into a British mine in search of a Lazarus pit to resurrect Bruce Wayne, and when he discovers previously unknown tunnels and ‘Batcave’ under Wayne Manor leading to the return of Bruce Wayne.

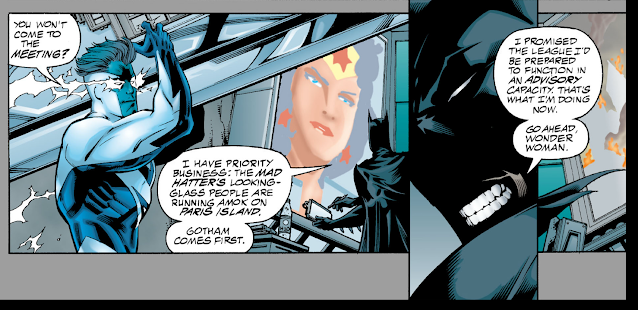

At the start of the JLA run Batamn tells the league that he’s only prepared to act in an “advisory capacity” because for him “Gotham comes first”. This is the restriction – self-imposed in this JLA story, but meta-textually one that has been imposed on Batman by a succession of writers, particularly since the ‘dark and gritty’ version of the character from the late 80s onwards – and it is part of Morrison’s mission in his run to break Batman out of this geographical restriction.

When the JLA are attacked by the villain The Key, the team are subjected to a neural virus that transports their minds to alternate lives. In Batman’s alternative he is living in retirement with Selina Kyle (Catwoman), and the mantle of Batman has passed on to Tim Drake with Bruce Wayne Jr as his Robin. This is a quite different outcome to the events in Morrison’s Batman run where Dick Grayson becomes the new Batman, with the son of Bruce and Talia Al Ghul, Damian, as his Robin – who in a potential future then goes on to become Batman himself. #8 also sees the phrase "Batman and Robin can never die", which, in the slighty different form of "Batman and Robin will never die!", will feature several times in the Batman run - and is probably the overaching message of the whole story.

In the Rock of Ages storyline, which pitches the JLA against Lex Luthor’s Injustice Gang, the latter approach their conflict as “the corporate takeover of the Justice League’. This, Luthor suggests, means employing the tactics of “identify their weak spots, destabilize their figureheads, headhunt the up-and-coming young hotshots’. However, they are undone by Bruce Wayne’s superior corporate knowledge and tactics. Not only is this echoed in that last third of Morrison’s run as Batman Incorporated take on Talia Al Ghul’s Leviathan organisation, Luthor’s tactics are employed by the latter during their war. Morrison has repeatedly used the idea of corporations within their work; The Invisibles, Marvel Boy, and Seaguy, to name just a few.

In a possible future Batman confronts Darkseid and is struck by the latter’s Omega Effect beams. Exactly the same thing will happen in Morrison’s Final Crisis which causes Batman to be thrown back in time, leading to the events of The Return of Bruce Wayne. However, in the JLA story the beams are said to send Batman “out of time, out of space..beyond what the gods even know”. The heroes save the day in their ‘now’, so that future never comes to pass, and we don’t get any follow up on this Batman’s fate – but it's interesting that Morrison re-ran the exact scene in Final Crisis but with (it appears) different consequences.

There are other connections to Morrison’s Batman in JLA – both specific and more general – though it also shares some of them with their other work through the years as well. The climatic storyline in JLA builds upon several of the shorter arcs throughout the series, and many of the previously featured characters return. The climax of The Return of Bruce Wayne builds upon the series to date, and ties together plot lines from the very first issue, though Final Crisis, and Batman and Robin. Whilst Batman Incorporated acts in many ways as a fresh start as it moves on from the Joker and Dr Hurt, it ultimately ends with huge conflict between the characters that featured in Morrison’s opening arc Batman and Son, whilst also includes many of the characters (re)introduced along the way. The JLA run also features characters from the New Gods – particularly in its final story – who are key parts of Final Crisis and its impact on Batman and his supporting cast. Interestingly, whilst the Joker does appear in JLA as part of Lex Luthor’s Injustice Gang, he has little more than cameo appearances and has a much more traditional presentation that he will in Batman R.I.P. – Morrison has little to say here about the Joker, saving that deeper exploration for his longer Batman project.

The weekly series 52 span out of the Infinite Crisis comic/event, following which the holy trinity of DC Comics - Batman, Wonder Woman, and Superman - look a year-long leave of absence (hence the title, it covered 52 weeks in the DC universe in 'real time'). At the conclusion of Infinite Crisis Bruce tells the other two-thirds of that trinity that he intends to 'retrace the steps I first took when I left Gotham. I'll be rebuilding Batman. But this time it's going to be different....I'm not going alone.' Accompanied by (at that time the only) Robins (Dick Grayson and Tim Drake), this sets up the premise of Morrison's mission for Batman - to turn him from the dark violent soldier-vigilante character he had become into a brighter better-adjusted superhero. Batman plays a very small part in the 52 series, but the few pages dedicated to him are incredibly important to what comes next. Indeed, in the omnibus reprints of Batman R.I.P. the relevant pages are included as a prologue of sorts, and therefore I will address these in their own blog and annotations rather than just summarising them here,

In the next blog I'll take a look at some of the Batman comics not written by Grant Morrrison that tie into their Batman run.

Mike

No comments:

Post a Comment